A couple of weeks ago I posted about a weird sauna experience which was especially surprising because everything had been so normal so far. And of course things started to get even weirder after that.

There is a Finnish band, Eläkeläiset, which makes humppa (it's a music style) "covers" of famous rock songs (in Finnish of course). Like this: original, cover. And apparently this band is a Thing in Germany. We went to see their gig, and it was a weird cultural experience.

However, this blog post is not about that band or that gig, but I have a real (kitchen) linguistic theme here:

Germans have a cute habit of using the pronoun "it" when they talk about a baby, even when he/she is their own and the gender of the baby is definitely known. Like this: "Our baby was born a month ago. It only sleeps two hours max at a time."

"It" has actually been used when talking about babies in English too, but it's nowadays getting rarer.

I'm not 100% sure (hey, this is kitchen linguistics), but I think that Germans use "it" when talking about babies because of the gender system of the German language.

German naturally has separate pronouns for he, she and it (er, sie, es), like in English. But since inanimate objects also have a gender in German, the pronouns are used a bit differently than in English.

For example, Germans say: "Ich habe einen Brief bekommen, aber ich habe ihn noch nicht gelesen." - "I got a letter, but I didn't read him yet." A letter is a masculine, so "he" is used when referring to it. So, he is used with masculine nouns, she with feminine nouns and it with neuter nouns.

I've never heard a German make a "I didn't read him yet" type of a mistake when speaking English. Maybe Germans have a mental model where all English nouns are neuter.

Baby is neuter, das Baby, in German, and that's probably why "it" is often used when talking about babies, but always in a loving tone of voice. I find it awesome because of two subtle connotations: 1) a baby is not a "real human" yet, but it will become one when it grows up 2) babies are genderless, i.e., their gender is irrelevant.

In Finnish, we only have one word (hän) for he and she, and a separate word for it (se). So, "hän" is for humans, and "se" is for non-humans. But in spoken language, we also say "se" when talking about humans, so we really need to use only one pronoun.

This is also the reason why I cannot get he / she / him / her / his / her right in English - mostly I just randomly choose a gender and rely on it being correct in 50% of the cases. This leads into epic utterances like "she got his act together".

But when I say "her wife" or "his boyfriend", I'm usually not confusing genders, because both exist in my circle of friends. And sorry, all transgender folks, I don't use the wrong pronouns because your gender is so confusing - I use the wrong pronouns for everybody.

Scientifically incompetent discussion about languages (mostly English, German, Finnish, Swedish...)

Sunday, 28 April 2013

Friday, 19 April 2013

Like burning the ice

Today I'm going to entertain you with Finnish sayings.

kuin paita ja peppu - like a shirt and a bum

Used to describe very close friends who do everything together. "They are like a shirt and a bum."

kuin jäitä polttelisi - like burning the ice

A suitably unenthusiastic reply to "how is it going". For example, "How's your work?" "Like burning the ice."

In Finland, if you're asked how it's going, you're not supposed to say anything overly positive. The scale is from "it's okay" downwards. So "like burning the ice" means that "oh well, nothing special to complain about, but it's work, so, you know, sometimes I'd rather just sleep in and not go to the office in the morning".

kuin ripulissa piereskelisi - like farting while having a diarrhea

An action that needs to be carried out extremely carefully.

I think I'll stop here, and say like we Finns say after a good party: "Kiitos ja anteeksi." - "Thank you and I'm so sorry".

kuin paita ja peppu - like a shirt and a bum

Used to describe very close friends who do everything together. "They are like a shirt and a bum."

kuin jäitä polttelisi - like burning the ice

A suitably unenthusiastic reply to "how is it going". For example, "How's your work?" "Like burning the ice."

In Finland, if you're asked how it's going, you're not supposed to say anything overly positive. The scale is from "it's okay" downwards. So "like burning the ice" means that "oh well, nothing special to complain about, but it's work, so, you know, sometimes I'd rather just sleep in and not go to the office in the morning".

kuin ripulissa piereskelisi - like farting while having a diarrhea

An action that needs to be carried out extremely carefully.

I think I'll stop here, and say like we Finns say after a good party: "Kiitos ja anteeksi." - "Thank you and I'm so sorry".

Sunday, 14 April 2013

Zwangsentspannt

Today I will hijack the language blog for telling about the weirdest thing I've done in Germany so far. When we moved the Germany, I had the problem that everything was so normal, and we didn't have any funny anecdotes to tell to our friends and family who stayed in Finland. Now, after 2 years, I have something to tell, so here we go...

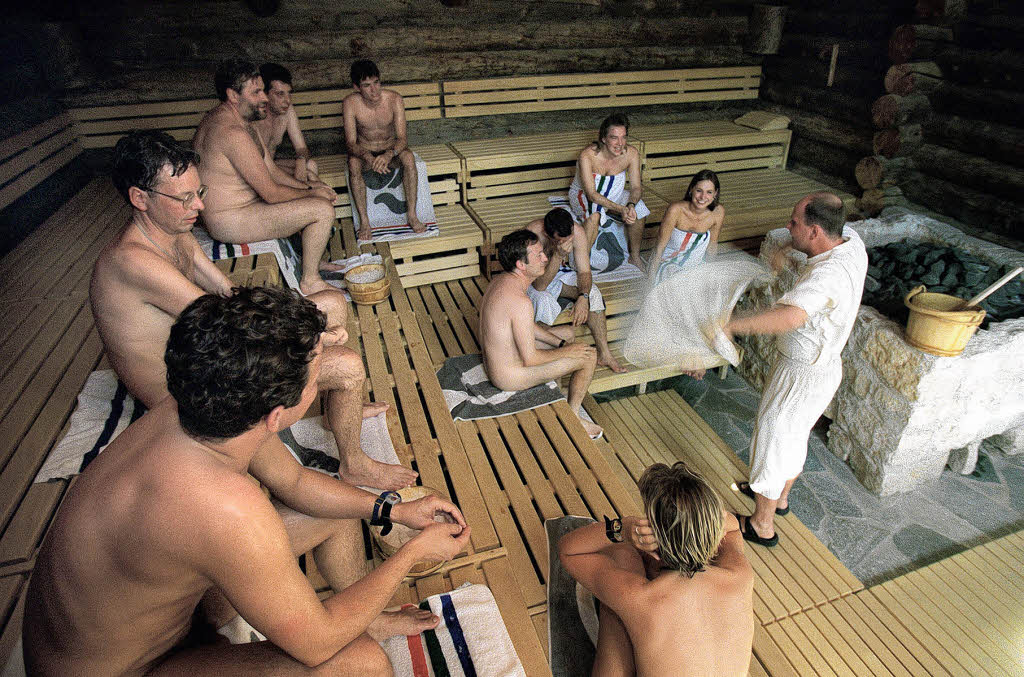

In most countries there is a form of entertainment where a naked person entertains an audience who is wearing clothes.

But in Germany, the inverse occupation also exists - Saunameister (sauna master) is a clothed person entertaining a naked audience by throwing water on the hot stones in a sauna, circulating the hot steam by waving a towel and flapping it in the air, and telling jokes on the go (because of the language barrier, I only understand a subset of the jokes, sadly). The most advanced Saunameister I've seen even uses a towel flag for the circulating, and that thing is torturously efficient.

You're supposed to find the experience relaxing (entspannend), if you don't, you will be "Zwangsentspannt" (forcefully relaxed).

Curiously, there is no good translation of "Zwang" in English, even though it translates perfectly well in other languages I know (tvång in Swedish, pakko in Finnish). Zwang describes something compulsory / unavoidable / something you must do, but it's not an adjective but a noun. You could say "wearing a helmet is compulsory" and "Zwang" would be the "compulsory" except that it's a noun.

There are also other Meisters in Germany: Bademeister (bath master) is looking after kids in a swimming pool and Hausmeister (house master) is approximately a janitor. Funnily, some Hausmeisters (but not all) are "vahtimestari" in Finnish, that derives from Wachtmeister (watch master), but Wachtmaster is something different than Hausmeister...

From the Finnish perspective, the Saunameister is exotic in a funny way, and the excessive nudity is only mildly culture shocking. So now to the weird stuff: Klangschalenaufguss.

Aufguss (literally "onpour", auf = on, guss = a noun from the verb "pour") is what Saunameister does: pouring water on the stones, and the related activities for circulating the steam.

Klangschale is apparently translated in English as "singing bowl" (never heard), and it's a metal bowl which produces sound when you hit it with a stick. Some esoteric stuff they say.

And Klangschalenaufguss is naturally an Aufguss where the Saunameister alternates between throwing water onto the stones and rings these bowls. I might have missed the esoteric benefits. I tried not to giggle.

The next weird thing doesn't have any linguistic connections, but I need to tell it nevertheless: The crazy Germans have a sauna with an aquarium in it. And soothing music. So you can watch the fish swim around and listen to the music while you sweat. Finns, let me reiterate: Germans have an aquarium in a sauna.

The experience culminated in Salzaufguss, (salt onpour), where you first do the first round of Aufguss (pouring the water and waving the towel) normally, then go out, rub salt on you skin, come back, and do one more round of Aufguss.

When standing outside (luckily the weather was warm), naked, rubbing big handfuls of salt on my skin, among 50 or so Germans doing the same, I said "This is the weirdest thing I've done in Germany so far".

Monday, 1 April 2013

Goodbye, linguistic cousins?

Helsingin sanomat, the main newspaper in Finland, published an interesting article about linguistics getting political in Hungary: The right wing Hungarians deny that Finnish and Hungarian are language relatives, since it doesn't fit their political agenda.

Since there is no English translation, I'll provide a pirate translation below. The original article is here (published 30.3.2013, written by Maria Manner).

Finnish is no longer a good language relative to Hungarian

Many Hungarians don't want to believe any more, that Finnish and Hungarian are language relatives. The right wing parties are writing a new, glorious history for Hungary, and the Finnish nation is considered too backwards to fit it.

"The claims about Finnish and Hungarian being language relatives are nonsense. It's just communist propaganda! In Finland, the school books have been revised and the old theory removed."

These claims surface frequently in today's Hungary. Online discussion boards and bookstores offer lot of information about Hungarian not being a Finno-Ugric language after all.

Finns, who take the relationship between Finnish and Hungarian as granted, are confused. What is happening to our language cousin?

After the fall of communism, the alternative theory has stricken through in Hungary, explains Johanna Laakso, a Finnish professor of Finno-Ugric studies from the university of Vienna.

"The Finno-Ugric heritage is seen as a plot of Vienna and then Moscow, an attempt to humiliate the Hungarians.", she says.

According to a popular view, Hungarians descend from glorious eastern warrior nations, Scythians or Hunns, and ancient high cultures, for example Sumerians. Even Hungarian students who have just enrolled into university to study Finno-Ugric studies might believe this.

"Even in universities, we need to put a lot of effort to get rid of these false views. My Hungarian colleagues say that many people believe in these alternative theories.", explains Laakso.

The relationship between Finnish and Hungarian was discovered in the late 17th century. A German doctor, Martin Fogel, found similarities in vocabulary and structures of the two languages. Hungarian János Sajnovics established a foundation to Finno-Ugric linguistics hundred years later.

According to modern linguistics, Finno-Ugric languages derive from the same base language which was spoken 4000 - 6000 years ago near the river Ural. Since then, the languages have diverged so much, that the similarities can usually be observed only by trained linguists.

In the beginning, Hungarians didn't think highly of their northern relatives. Since the Middle Ages, they have regarded themselves as descendants of Hunns. The northern nations were seen as "wildlings stinking of fish" who didn't have a glorious history of warfare, says Laakso. The Finnish nation was seen as too backwards.

During the socialist era, Hungarian being a Finno-Ugric language was not questioned, and the alternative views were kept alive only by immigrant Hungarians.

When the communism and its truths fell, the linguistic relationship started to look like communist propaganda, too.

The alternative science is not only alive in Hungary. In Finland, Kalevi Wiik has developed a theory that the ancient Finns were the main nation of northern Europe and their language was the bridge language, lingua franca, of the ancient nations. According to Laakso, the position of pseudo science is particularly strong in Hungary, though.

Hungarians are now rewriting the history, not only based on science, but also on patriotic emotions.

The right wing extremist party, Jobbik, has demanded that the origins of the Hungarian language need to be re-evaluated. The popular right wing nationalist party, Fidesz, is sitting between two stools: Part of the politicians flirt with the alternative history. Two weeks ago, a Fidesz politican said in the parliament that there is no commonly accepted theory supporting the relation between Finnish and Hungarian.

"The real Hungarian linguists don't question the Finno-Ugric origin. But politicians, artists, and many others don't want to believe in it, but instead they support a new, more romantic version of the Hungarian history", says Marianne Bakró-Nagy, a professor from Szeged, Hungary.

The people longing for a glorious history try to get support from genetics.

For example, the Finns are genetically closer to people in the Netherlands than in Hungary.

But the language and the genes don't follow the same routes.

"These people are not interested in the fact that being genetic relatives has nothing to do with being language relatives", says Bakró-Nagy.

Hungarian doesn't have close language relatives. Maybe that's why Hungarians have difficulties to understand, what being language relatives means.

A Finn can compare Finnish to Estonian, meänkieli dialects and the Karelian language, and that makes it easier to understand the different degrees of being language relatives.

The most vocal opponents of the Finno-Ugric heritage are sending hate mail to researchers. Laakso says that many Hungarian Finno-Ugric researchers are afraid of negative reactions, and try not to mention their field of study when meeting new people.

People have also called Laakso a racist and said she's just being envious.

"Many messages I get are clearly from people who feel hurt. It's the same thing with Creationists: if the science doesn't support their holy world view, it must be part of an evil conspiracy.", she says.

A Hungarian linguist, László Fejes, says he gets feedback from the opponents of the Finno-Ugric heritage all the time. He hosts Nyelv és Tudomány, a portal for linguistics and science and has tried to get rid of the false views. Some time ago, Fejes asked his colleague Laakso to send him a pile of Finnish school books, to show that the Finno-Ugric heritage has not been abandoned by Finns.

"It's an old and widely spread legend, but before us, nobody has shown school books to the public.", Fejes explains via e-mail.

There's no consensus on what's the origin of the Hungarian language, according to the new theory.

"The anti-Finno-Ugrics don't seem to be able to decide if they're from Egypt, Mesopotamia or the Philippines. Everything goes, as long as it's not Finno-Ugric", says Laakso.

Annele Apajakari, who worked for the Finnish Navy in Hungary, met the language relative problem often. She says it's mostly a difference between generations.

"Hungarians 35 years old or older who went to school in the old system, know Kalevala (the Finnish national epic) and Väinämöinen (its main hero).", she says.

The younger Hungarians have different views.

"Once I said that our languages are related, and people laughed at me. A good friend of mine, who is well educated and 26 years old said, that no, Hungarians descend from the Schythians, an Asian warrior nation."

Hungarians don't have anything against Finns, though - on the contrary. Apajakari says that Hungarians still think very positively of the Finns.

Our common linguistic roots just don't happen to fit the new patriotic history, since there are more glorious options on the table.

Since there is no English translation, I'll provide a pirate translation below. The original article is here (published 30.3.2013, written by Maria Manner).

Finnish is no longer a good language relative to Hungarian

Many Hungarians don't want to believe any more, that Finnish and Hungarian are language relatives. The right wing parties are writing a new, glorious history for Hungary, and the Finnish nation is considered too backwards to fit it.

"The claims about Finnish and Hungarian being language relatives are nonsense. It's just communist propaganda! In Finland, the school books have been revised and the old theory removed."

These claims surface frequently in today's Hungary. Online discussion boards and bookstores offer lot of information about Hungarian not being a Finno-Ugric language after all.

Finns, who take the relationship between Finnish and Hungarian as granted, are confused. What is happening to our language cousin?

After the fall of communism, the alternative theory has stricken through in Hungary, explains Johanna Laakso, a Finnish professor of Finno-Ugric studies from the university of Vienna.

"The Finno-Ugric heritage is seen as a plot of Vienna and then Moscow, an attempt to humiliate the Hungarians.", she says.

According to a popular view, Hungarians descend from glorious eastern warrior nations, Scythians or Hunns, and ancient high cultures, for example Sumerians. Even Hungarian students who have just enrolled into university to study Finno-Ugric studies might believe this.

"Even in universities, we need to put a lot of effort to get rid of these false views. My Hungarian colleagues say that many people believe in these alternative theories.", explains Laakso.

The relationship between Finnish and Hungarian was discovered in the late 17th century. A German doctor, Martin Fogel, found similarities in vocabulary and structures of the two languages. Hungarian János Sajnovics established a foundation to Finno-Ugric linguistics hundred years later.

According to modern linguistics, Finno-Ugric languages derive from the same base language which was spoken 4000 - 6000 years ago near the river Ural. Since then, the languages have diverged so much, that the similarities can usually be observed only by trained linguists.

In the beginning, Hungarians didn't think highly of their northern relatives. Since the Middle Ages, they have regarded themselves as descendants of Hunns. The northern nations were seen as "wildlings stinking of fish" who didn't have a glorious history of warfare, says Laakso. The Finnish nation was seen as too backwards.

During the socialist era, Hungarian being a Finno-Ugric language was not questioned, and the alternative views were kept alive only by immigrant Hungarians.

When the communism and its truths fell, the linguistic relationship started to look like communist propaganda, too.

The alternative science is not only alive in Hungary. In Finland, Kalevi Wiik has developed a theory that the ancient Finns were the main nation of northern Europe and their language was the bridge language, lingua franca, of the ancient nations. According to Laakso, the position of pseudo science is particularly strong in Hungary, though.

Hungarians are now rewriting the history, not only based on science, but also on patriotic emotions.

The right wing extremist party, Jobbik, has demanded that the origins of the Hungarian language need to be re-evaluated. The popular right wing nationalist party, Fidesz, is sitting between two stools: Part of the politicians flirt with the alternative history. Two weeks ago, a Fidesz politican said in the parliament that there is no commonly accepted theory supporting the relation between Finnish and Hungarian.

"The real Hungarian linguists don't question the Finno-Ugric origin. But politicians, artists, and many others don't want to believe in it, but instead they support a new, more romantic version of the Hungarian history", says Marianne Bakró-Nagy, a professor from Szeged, Hungary.

The people longing for a glorious history try to get support from genetics.

For example, the Finns are genetically closer to people in the Netherlands than in Hungary.

But the language and the genes don't follow the same routes.

"These people are not interested in the fact that being genetic relatives has nothing to do with being language relatives", says Bakró-Nagy.

Hungarian doesn't have close language relatives. Maybe that's why Hungarians have difficulties to understand, what being language relatives means.

A Finn can compare Finnish to Estonian, meänkieli dialects and the Karelian language, and that makes it easier to understand the different degrees of being language relatives.

The most vocal opponents of the Finno-Ugric heritage are sending hate mail to researchers. Laakso says that many Hungarian Finno-Ugric researchers are afraid of negative reactions, and try not to mention their field of study when meeting new people.

People have also called Laakso a racist and said she's just being envious.

"Many messages I get are clearly from people who feel hurt. It's the same thing with Creationists: if the science doesn't support their holy world view, it must be part of an evil conspiracy.", she says.

A Hungarian linguist, László Fejes, says he gets feedback from the opponents of the Finno-Ugric heritage all the time. He hosts Nyelv és Tudomány, a portal for linguistics and science and has tried to get rid of the false views. Some time ago, Fejes asked his colleague Laakso to send him a pile of Finnish school books, to show that the Finno-Ugric heritage has not been abandoned by Finns.

"It's an old and widely spread legend, but before us, nobody has shown school books to the public.", Fejes explains via e-mail.

There's no consensus on what's the origin of the Hungarian language, according to the new theory.

"The anti-Finno-Ugrics don't seem to be able to decide if they're from Egypt, Mesopotamia or the Philippines. Everything goes, as long as it's not Finno-Ugric", says Laakso.

Annele Apajakari, who worked for the Finnish Navy in Hungary, met the language relative problem often. She says it's mostly a difference between generations.

"Hungarians 35 years old or older who went to school in the old system, know Kalevala (the Finnish national epic) and Väinämöinen (its main hero).", she says.

The younger Hungarians have different views.

"Once I said that our languages are related, and people laughed at me. A good friend of mine, who is well educated and 26 years old said, that no, Hungarians descend from the Schythians, an Asian warrior nation."

Hungarians don't have anything against Finns, though - on the contrary. Apajakari says that Hungarians still think very positively of the Finns.

Our common linguistic roots just don't happen to fit the new patriotic history, since there are more glorious options on the table.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)